Copyright André Seidenberg, Zurich, June 2024

The salvation of the world or just fewer problems? Both questions are discussed in this book.

The Swiss opioid crisis of the last century showed successful elements in dealing with addiction problems. The doctor’s practical experience leads to concrete suggestions and links them to the most fundamental questions of reflection on life.

Sucht[1], the German word means both addiction and dependency. But Sucht sounds like search, seeking and looking for something (Suchen) and we alliterate desire and longing for (Sehnsucht), temptation (Versuchung) and plague (Heimsuchung). The origin of the word is in fact the same as plague and illness (Seuche and Siechtum).

When your thoughts get so cought up in something, that everything else seems worthless compared to it, then you are trapped in addiction. That is Sucht. Sucht is the end of many other things, which might have been possible. Addiction is where all that’s left is the little big thing in which your whole mind and most of your being is trapped. Sucht is misery, real, terrible, terrifying, disastrous and destroying.

Switzerland is a conservative, neatly organized, small and beautiful country in the heart of Europe. Perhaps you know about Swiss independence of the EU, our alpine mountains, our extrodinary wealth, Swiss banks, chocolate and watches. Switzerland is proud of ist freedom. Similar to the US, Switzerland is a confederation of 26 cantons. In 1848, we adopted significant parts of the U.S. constitution to conform it to our centuries-old democratic traditions of popular assemblies, popular initiatives and plebiscites.

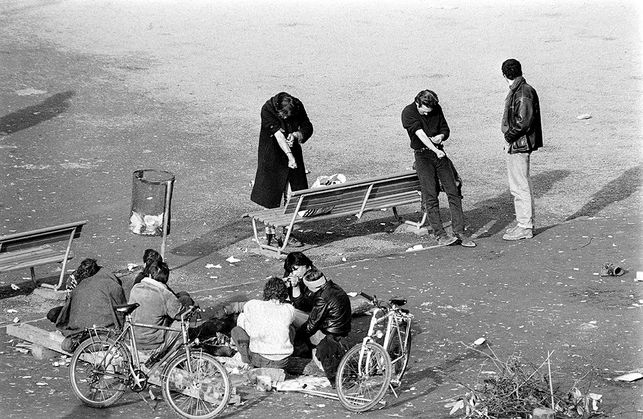

Like the United States today, Switzerland was affected by the worst drug crisis ever in Europe in the 1980s and 1990s. We had surpassed all Europe’s drug addiction and HIV rates. The catastrophe was visible on our streets, an unbearable misery, horror and anger to the public.

Picture: Gertrud Vogler (Sozialarchiv Zürich)

The Platzspitz Park behind the main station Zurich was the center of the disaster, a neelde park, an abyss and a black hole of drugs. But Switzerland prevailed. We overcame all of these difficulties. Nowadays you hardly find any open drug scenes in Switzerland. Why are the United states unable to achieve the same? Long ago, all means to overcome an opioid crisis scientiffically proved their effectiveness and cost efficiency sufficiently. The US drug policy ignores this and its detrimental contribution to the individual interests of addicts and the public interests of order, as well as instabilities and war in foreign countries.

Switzerlands history of Sucht and drugproblems became a significant part of my life. As a doctor, I personally met three and a half thousand opioid-dependent people. I knew, accompanied and cared for them sometimes for half their lives. They were trapped in their opioid addiction from which they could hardly escape. Most learned to come to terms with their endless suffering. The addiction didn’t let go of them, the suffering wasn’t cured, but it was contained. No healing, but life was possible again. The restrictions that accompany Sucht were pushed back, contained, in the smallest possible place in their lives. This help may seem small, but more often than not it has been crucial.

A hope-seller may be a successful doctor or a politician, but as a consequence there will come the moment, when he or she will be a bad doctor. This book is not edifying and makes no promises. Perhaps it will help you, dear reader, to gain a little more reality.

Sucht, addiction often is a unhealable disease. Addiction to opioids nearly never heals. With other drugs and addictive means many people find a way out, but scars in body and soul often remain. Like many other diseases, addiction cruelly finds its endless disastrous way. And even worse: Sucht, addiction and dependence are fundamentally based in our selves and a concern to everybody.

Sucht is as human as it can be. Only man can bring animals or humans in addictive dependencies. Addiction is deeply founded in our biology, but only humans can give himself away in an addicted manner.

Sucht is voracious and threatens to destroy us humans. Sucht might end the human history as we are able to ignore the finiteness of earthly resources in our activities. Our thoughts and actions are fundamentally corruptible by addiction. Sucht is a basic conditionality of our thinking and our being, we need to know more about and think more about.

Extasy by intoxication is a well-known human phenomenon. Throughout human history scarcity was predominat. That’s why addiction has only been possible for everyone for a few decades. Only nowadys Sucht has become a problem that affects us all. We are all addicted to something: nicotine, alcohol, sleeping pills, sedatives, food addiction, anorexia, sex addiction, gambling addiction, TV, cell phone, work, sport, money, striving for power, being bossy, etc.

All of our motivation is controlled by the reward system. There is no beauty and no truth independent of dopamine releases in the nucleus accumbens. The corruptibility of our thinking is obvious. It’s worth thinking about addiction. Thinking about addiction is necessary out of sheer self-preservation.

Our existence, our striving, is in life, in this world, not in transcendence, nor in death nor afterlife. Hope, the only hope, is that we are on the side of life as long as we live. There is no other hope. Outside life, outside existence, is not the other, but nothingness.

Who knows personally where they will stand when death calls? For the doctor, the truth is only the guiding principle of his actions until death. It is not uncommon for the doctor to encounter the boundless horror. Fear can damage our thinking. But fear of what terrible things could be, what terrible things actually exist, this fear is justified and appropriate. And almost every horror imaginable actually exists. Any reduction of reality can be harmful.

«The affections of hope and fear cannot be good in and of themselves»[2], said Baruch Spinoza[3]. Hope, terror and danger are only good or bad insofar as our emotions are affected. «He who is guided by fear and does good to avoid evil is not guided by reason.»[4]

What means Spinoza’s term Conatus, desire, striving, craving? What is this drive that guides us throughout life, but can also lead us astray? What drives us until we no longer know what to do, when we are driven, driven into a corner? Again and again we find this striving in everything, in everything we look for, in everything we think is good, where we want to go, what we find true, what we find beautiful, in everything we are.

Sucht, addiction, the constant drive by our needs, points to our subjectivity. But neither the terms Sucht, nor addiction nor compulsion capture the subjective. Like Spinoza with his concept of conatus, Sigmund Freud pointed to the omnipresence of the subject with his concept of the Id and relied on the healing power of consciousness with his demand « where It was, I should become » [5].

The gap and dichotomy between life and death exists, but only in life before death.

The joy of being, being a part of this unbound life, which we want to infinity… To encounter others in existential situations is a privilege, a source of serenity and a heavy burden for a doctor. Conatus for Spinoza also means self-preservation; so what should guide a physician? What is more important: Hope or Truth, Freedom and Human Rights?

Religion, mysticism and alternative sorcery are seen as harmless private aids. But any obscurantism can be harmful. This book sheds light on some religious matters too, but has no religious intent. For traditional Judaism, God contains the whole world, from and to infinity[6]. Gods all-encompassing infinity extends within this world and connects the subjective to the objective world. Spinoza also saw himself as part of the infinity of God’s nature. This thought seemed comforting to him. Although Spinoza wanted to banish all obscurantism from reality, he sought to find salvation in it.

Stripping the world of all superstition, fear and hope[7] leaves no absolute truth, only conditioned truths. The all including truth lies in infinity, which is desired but not reached by humans.[8]

My dear doctor, don’t we need a common truth? How do you want to treat your patients, to treat the diversity of human beings? Wouldn’t you be unable to act without a scientifically common, universal and concrete truth?

Karl Marx rightly asked about the justified practice of the philosopher: «The philosophers only interpreted the world differently; but the important thing is to change it.»[9] But Marxism has lost sight of the people. The question of what is to be done, however, remains necessary. And for every physician this question is emediate, practical and enevitable. Even if despair is immense and you need to do something, you as a physician must not lose your mind.

What is to be done in this world?[10] For a physician, the questions of life arise in very tangible terms. Even during the time of his studies, friends and later patients of the author were neglected, sick, disappeared, impoverished in real and other prisons and died. Even more people gave up the search for freedom and everything else, put it in a corner, postponed, but missed it with longings for a lifetime. Excess is not the same as addiction. But addiction is one of the prisons we’re talking about here.

Ecstasy and intoxication are well-known human phenomena. During nearly the whole human history regned scarcity. Addiction has become possible for everybody only since a few decades. Sucht concerns us all today. Nearly everybody is dependent of something: nicotine, alcohol, sleeping pills, downers, eating disorder, anorexia, sex, gambling, gaming (Esssucht, Magersucht, Sexsucht, Spielsucht), TV, smart-phones workaholics sports, money, bossyness, power, etc.

All of our motivation is driven by the reward system. No beauty and no truth is independant from dopamine releases in the nucleus accumbens at the base of our brain. The corruptibility of our thinking is obvious. Thinking about addiction is worth it and necessary, out of sheer self-preservation.

The power and strength of a society can be measured by its ability to also include and maintain as members all humans at its borders. Humans with diseases, illnesses and disabilities are not excluded but cared for. The appreciation of every single person is a central thought of the West and a fundamental motive of many doctors.

To save one human life, means to save a whole world.[11] And what better thing can one do in this world? Even a non-believing person faces this world that asks him: Where are you?[12] In every human face you look at you will find these questions.

There are many lines and bows of thought to be drawn, many thinking vehicles to be presented, and many materials from philosophy, biology, medicine, physics, mathematics and even theology have been brought together. A good book is like a hologram in which the entire content lights up in every part. I don’t achieve that. The structure of the book is more like the double helix of a chromosome strand. Not only is it read linearly and translated into the language of proteins, but recursively the process always goes back to this or that part in order to regulate further production. The twists, ups and downs of thoughts are not intended to confuse you, but rather to entertain you and stimulate your thoughts about the conditionality of thinking. Be patient and enjoy!

Content

Preface. 2

Freedom.. 7

Sucht 10

Conditionalities. 14

Spinoza. 17

Hologramm.. 25

Reward System.. 37

Switzerland. 44

Abstinence. 52

Civilisation. 62

Rausch. 65

Francesca. 66

Drug Policy. 67

Inhalativa. 72

Cocaine. 74

Jim.. 78

God. 81

Unity. 85

Security. 92

Individuality. 96

Truth. 98

Leviathan. 102

Scarcity. 111

Thinking. 113

Timetable. 120

[1] Say sookht

[2] Spinoza, Ethics (Ethica Ordine Geometrico Demonstrata), posthum, Ethics IV.47

[3] Baruch Spinoza, Benedictus de Spinoza, 1622-1677

[4] Spinoza, Ethics IV.63

[5] Sigmund Freud, Die Traumdeutung, 1900

[6] אין סוף Ein Soph, endless infinity

[7] Spinoza, Tractatus theologico-politicus TTP, Preface: People are often under « the spell of superstition… [since] they cannot take a plan and… most of the time vacillate miserably between hope and fear, their mind is generally inclined to believe anything… Under the spell of superstition… they invent countless things and interpret nature in strange ways, as if it shared their madness. »

[8] However, Spinoza thought of this infinity in such close proximity that his ascetic life and thought appeared to be spiritually permeated by it. The conditionality of human existence did not concern Spinoza’s thinking very much.

[9] Karl Marx: Thesen über Feuerbach, 1845, 11. These.

[10] Wladimir Iljitsch Lenin Что делать? 1902, «What is to be done?» was his concise and clear question. The title goes back to the novel by Nikolai Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky (1828 – 1889), written in tsarist prison in 1863.

[11] Talmud, Sanhedrin 37a

[12] הנני Hineni, Here I am! says the bible in the Genesis 22. תיקון עולם, tikkun olam, the healing of the world.