The bad and evil in the German words Sucht (addiction), Seuche (plague), and Siechtum (sickness) still pervades most usages today. Addiction and infirmity stood in contrast to salvation and holiness. But even with the words holy, salvation and saints, a desperate aggressive violence points to blood, death and destruction which emerge from the cracks of organized hope.

Up until 10,000 years ago no human has ever become addicted. Addiction can only arise through constant abundance; our biology has adapted to shortage. Addiction is not in our biological plan. Addiction is inherent in our biology, but wasn’t possible in the real world of a vertebrate until a human came along. Only modern people can create an addictive situation and corrupt the reward system.

In the Neolithic Revolution, more than 10,000 years ago, humans first achieved the prerequisites for addictions. Grain was domesticated for the first time and was available in larger quantities. Even then, for the construction of the huge temple complex in Göbekli Tepe in Southeast Anatolia, many people not only had to be fed, but also motivated. Could gods do this alone?

It is not unlikely that lavish festivals with beer opened the agrarian age. Perhaps at the end of the Paleolithic, brewing beer was initially more important to people than baking bread. Alcohol preserves the high-calorie beverage beer in a ready-to-drink state for a long time, and alcohol can pleasantly put most people into extasy. An agricultural society can feed more people but health and longevity suffer.

Perhaps grain is not just food, but the first addictive substance that could make people dependent. For economic reasons, only a small number of people may have maintained sustained alcohol consumption at the beginning of the Neolithic. Do not only grim gods look at us from the stone figures, but also the first addicts of mankind, powerful drunken priests in Delirium tremens[1]?

Perhaps it was not only man who domesticated the grain, but vice versa, the grain took man into dependent servitude and condemned him to work by the sweat of his face? Is that what tells the biblical story of the farmer Cain, who killed his firstborn brother Abel out of envy and jealousy?

Over the past millennia, people have learned to brew many other alcoholic beverages from sugary grains and fruits of all kinds: beer, wine and berry schnapps. Few people in ancient Egypt, Babylon, Rome or China were able to do anything more than occasional excessive drinking; the alcohol addiction was a rarity and only recently became a mass phenomenon.

Agricultural societies discovered other addictive substances than alcohol too. In Swiss stilt houses, archaeologists found 6,000-year-old traces of the cultivation of Papaver sonniferum, the opium poppy. Cannabis sativa, hemp, has also been cultivated in this country since times immemorial. Textiles were made from hemp fibers. The medical or hedonistic use of cannabis is less well documented in prehistoric times. Addicted use of cannabis and opium poppy is unlikely in prehistoric times.

Obesity became a deadly disease in a broader segment of the global population. Earlier humans died from malnutrition and almost never from overnutrition. For the generations before us, obesity was a fatal disease for only a few very rich people. Even in ancient times, the Middle Ages and up until modern times, people died en masse from malnutrition; death as a result of overeating was rare. ⅔ of adults in the USA are now overweight.

Coca and tobacco were known and common in the agricultural societies of the Americas many centuries before the arrival of European colonizers. However, addictive consumption only arose with the more intensive cultivation of these plants through colonization. Supposedly, slaves and today’s poor workers are able to work more persistently in the heights of the Andes. Miners in the Andes are said to spend a fifth of their income on coca, bringing them to the brink of starvation. Near the subsistence level, obtaining cocaine competes with obtaining enough food.

Until recently, only a few people could afford to become addicted. In the 18th and 19th centuries, for the first time, a significant number of people became dependent on addictive substances. It was only with the Industrial Revolution that masses of industrial workers became dependent on daily alcohol. Slaves from Africa enabled cheap agricultural mass production: sugar cane was grown in Central America, rum was cheap and contained a lot of alcohol. Alcohol addiction as a mass phenomenon has developed over the last two or three hundred years.

Nicotine addiction has been possible for the upper class since the beginning of modern times. Pipes and cigars are difficult to smoke during most work. Cigarettes were mass-produced for workers in the 20th century. Most addicts smoke around twenty cigarettes a day. This means they avoid suffering from withdrawal symptoms during their day. In the last century, they were able to maintain their addiction on a large scale in a socially tolerated manner.

Dependencies on morphine, heroin or cocaine are even more recent developments. Addiction has developed in mutual causality with colonization and capitalism. The drug wars over opioids and cocaine developed directly from these roots and even today the power structures in the drug wars can be analysed against this background.

Until recently, only a few people could become addicted. It was only with industrialization in the 19th century that a significant number of people became dependent on addictive substances. Chemistry and other scientific and technological advances have produced new and more effective drugs for less than 200 years. Opioids such as heroin and morphine are obtained more or less synthetically from opium. In 1806, morphine was first isolated from opium by the German pharmacist Friedrich Wilhelm Sertüner. Heroin was brought onto the market by the Bayer company in 1898 as a supposedly non-addictive painkiller and panacea. Cocaine was discovered in 1860 by Albert Niemann in Göttingen. Pasta de coca is extracted from the coca plant and through simple chemical transformations it is converted into cocaine in an injectable or inhalable form.

The consumerist age is still very young. Two or three generations ago, only a few women and probably only a minority of men were addicted to any addictive means. Today’s variety of addictive substances and offers is a phenomenon of the very latest times. Our mammalian reward system is being serviced and corrupted across all channels of the consumerist age. The industrial production of goods and services today covers almost all demands. Goals for which our ancestors had to make great efforts and which often remained unattainable are now achievable to most people. Food, drink, sugar, salt, warmth, pain relief, sex, thrills, stories, whatever already earlier humans desired, is now within the reach of vast numbers of people in an abundance unimaginable until recently. Today almost everyone is addicted in some way. The Internet has us all on our toes: Google, Microsoft, Facebook, BlaBlaBlot, Insta, TikTak, XY and www.what-ever.dot know exactly what we are looking for, caving for, what we like and love. They link to our most intimate system, the reward system.

Until the middle of the last century, only a minority of people were addicted to something. Today, most people in developed are addicted to at least one addictive substance or means: tranquilizers, sleeping pills, obesity, anorexia, shopping, beauty obsession, television, cell phones, sex, gambling. We all have to regulate our appetitive behavior with our minds. We are all faced with existential challenges and hardly anyone is never overwhelmed. Our naturally ever-excessive desires are no longer limited by the lack of options.

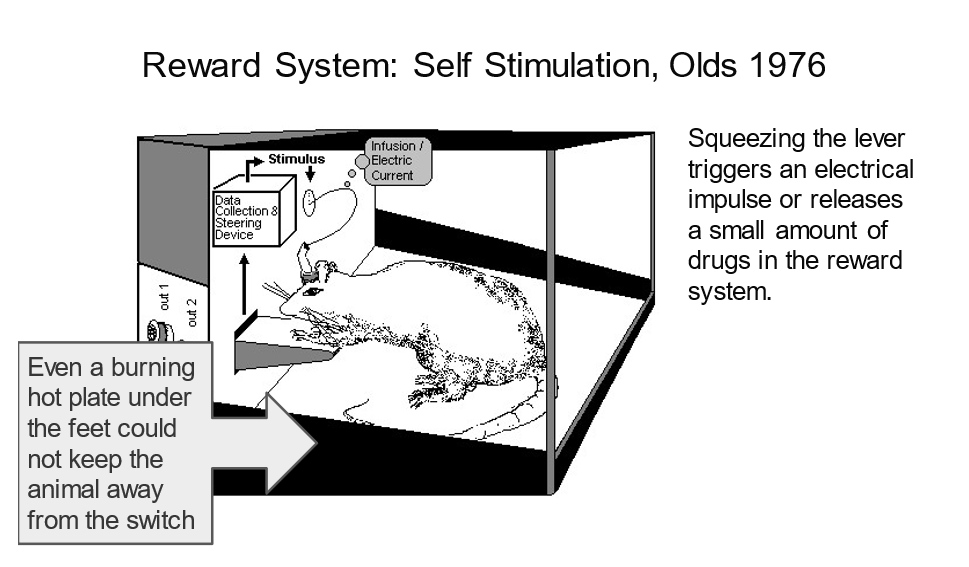

Sucht is the corrupt reward system, the overly direct access to the dopamine release switch. Not just junkies, everyone today faces the daily task of grappling with these addictive always-on offers. We all can no longer fully resist. How could we? Since our basic needs are no longer sufficiently regulated by the reward system on the one hand, and the conflicting demands of the environment, the scarcity of goods, on the other hand. Anonymous forces took hand on the levers to steer our reward system. Only for a brief period in our newest evolutionary history, we humans begin to resemble the rat in Olds‘ self-stimulation experiment.[2]

The mind, the ego, our organ of truth, the place where we make our decisions, are intimately connected to our mammalian reward system at the base of our cerebrum. There is allways a choice about what stimuli we allow to shape our decisions and to what extent. But our choices are always limited and always at risk.

Sigmund Freud chose the sexualized term libido to talk about people’s desires, wishes and aspirations. With libido, Freud focused on repressed sexuality as the main problem of his time. Spinoza’s term conatus encompasses all human motivation and the term Sucht or addiction points to the other side of the coin of our unbridled desires, wishes and aspirations.

Sigmund Freud found that the ego is not master in its own house.[3] The subject and the liberal humanism that puts the human being, each one of us, at the center of the world are under pressure. This is not a crisis or weakness of the Enlightenment, but its essence. We, no one else, every one of us, is challenged.

Desmond Morris,[4] described the sexual obsession of man. Sultans and other rulers may have been able to live out their sexuality in an addictive way with harems. But it was only in the last few decades that sex as an addictive activity became accessible to the masses. The Internet increased the availability of sex, primarily through pornography and ubiquitous contact mediation, to a previously unimaginable extent. The pill and other contraceptives allow a large proportion of women to have a much less inhibited sex life than before. However, the needs of female desire have only been partially alleviated. The sexual weariness, reminiscent of addiction-related damage, is discussed in the arts pages and in relationship guides. Sexuality can teach us how the evolution of our phenotype and our cultures can regulate and control the boundaries of addiction.

Facing Sucht, our problem resembles the fairy tale of Baron von Munchausen, who was able to pull himself out of the swamp by his own hair. How do we get out of our problems with addiction, individually and as society. How can Count Münchhausen pull himself and his horse out of the swamp by their own hair? How do we get healthy? How can we survive and live at all?

What is addiction if we are all addicted or at risk of becoming addicted? Cultural descriptions of an addictive personality[5] are neither individually nor socially helpful or curative. Biology and medical experience provide better answers to the question of what to do.

In Switzerland in the 1980s and 1990s, addiction and its consequences were the number one public issue. It was the time of the Swiss opioid crisis. Sucht concerns all societies worldwide today. Addiction is a issue that is currently discussed little and perhaps too little. Addiction has become a fundamental condition of our existence and our thinking.

[1] Delirium tremens: An acute confusional state caused by heavy chronic alcohol consumption. https://www.dainst.blog/the-tepe-telegrams/2016/05/05/losing-your-head-at-gobekli-tepe/

[2] James Olds, 1922-1976, Neurophysiologist, discoverer of the reward system.

[3] Sigmund Freud, Eine Schwierigkeit der Psychoanalyse, 1917: After Copernicus‘ cosmological insult that the earth is not the center of the world, and Darwin’s biological insult that we belong to the animal kingdom, Freud’s own psychological insult is the third fundamental insult to humanity.

[4] Desmond Morris, The Human Sexes: A Natural History of Man and Woman, 1997

[5] Albert Memmi 1920-2020. Tunesian Jewish Author. Albert Memmi, La Dépendance: Esquisse pour un portrait du dépendant – Babelio, EAN : 9782070289202; GALLIMARD (11/09/1979) Qui est dépendant ?

Tout le monde, répond l’auteur, après un étonnant inventaire : l’amoureux et le joueur, le malade, le fumeur, le buveur et l’automobiliste, le croyant et le militant, nous sommes tous, chacun à sa manière, dépendants.

De qui ou de quoi peut-on être dépendant ? À peu près de n’importe qui ou de n’importe quoi : on peut s’attacher aussi bien à une femme, à un homme ou à un chien, à une collection de papillons, à son travail, à la montagne, à un parti ou à Dieu. Il n’y a là aucun goût du paradoxe. Interrogeant sa propre expérience comme les expériences d’autrui, Albert Memmi montre que la dépendance est une fascinante évidence. Elle éclaire d’une manière inattendue la décolonisation, les relations actuelles entre les sexes et les œuvres de culture.

Who is addicted?

Everyone, answers the author, after an astonishing inventory: the lover and the gambler, the sick, the smoker, the drinker and the motorist, the believer and the activist, we are all, each in our own way, dependent .

To whom or what can we be dependent on? Almost anyone or anything: you can become addicted to a woman, a man or a dog, to a collection of butterflies, to your work, to the mountains, to a party or to God. There is no taste for paradox here. Questioning his own experience as well as the experiences of others, Albert Memmi shows that dependence is fascinatingly obvious. It sheds light in an unexpected way on decolonization, current relations between the sexes and works of culture.